Here are some true things about Maine Quilts: 250 Years of Comfort and Community.

Here are some true things about Maine Quilts: 250 Years of Comfort and Community.

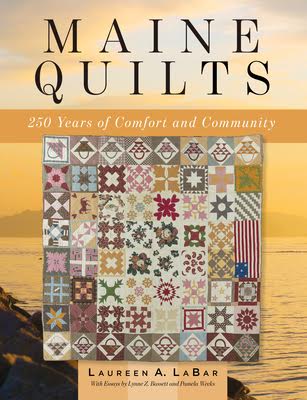

1) It is a sumptuous and informative history by Maine State Museum Curator, and one time DDG staffer, the renowned and fabulous Laurie LaBar!

2) Laurie is a modest person, but the exalted character of this coffee table history book will strain her self effacement.

3) The book’s levels of engagement, beauty, and edification are precisely equal as determined by scientific principles.

4) We have a little interview with the author for you below.

Kenny: What was the most entertaining thing you learned while researching your book.

Laurie: I learned that my colleagues across the country are a Lot of fun to spend time with! Oh… about quilts? Yes… I learned that Peter Max, the great psychedelic and pop-art artist, is a time-traveller, who, in an attempt to escape the madness and hype of the late 1960s travelled 100 years back in time to Alexander, Maine. There, in 1868 he collaborated with Anne Cotter to make a quilt that has stars and moons and flowers, leaves and birds, and is as groovy as anything Max ever painted. However, he found that the music and the social scene of rural 1860s Maine was much less fun than that of the 1960s. So he returned to 1968 and became a mind-numbingly rich and famous artist, inspired in no small part by his sojourn with Mrs. Anne Cotter of Downeast Maine. Oddly, this story was not passed to Anne’s granddaughter, who gave us the quilt. I can only assume that is because Anne’s daughter didn’t remember it because she was only three years old in 1868. So I could not report this discovery in the book, alas.

Also, quilt researchers are a lot of fun to spend time with. Did I say that already?

In all seriousness, the things that most delighted me were the quilts themselves, and the ways so many of them countered my expectations. I love the whimsey of the Cotter quilt (made, so far as we know, without input from Peter Max). There’s a block in the 1850 Bark Messenger quilt from Cumberland Center that is a favorite: it is a wee branch of a pear tree with leaves and two pears. And below them, the same size as the pears, is a sheep. It is so sweet and funky and folky. A block in another quilt made by the same group features a 3-D silk cigar. Even though I search always for the ways a quilt can reveal information about the people who made it and their lives, the visual aspects of the quilts delight me.

Kenny: If you could take one of the museum’s quilts home to keep which would it be?

Laurie: Well, that would of course be utterly unethical, so I won’t even consider any of the Maine State Museum’s quilts (though Anne Cotter’s quilt is a personal favorite). And of course, the more you learn about quilts the more you discover how very fragile old cottons and dyes are, so I would choose a wool quilt. As long as you don’t get a moth infestation, the fabrics are pretty rugged, and the structure of the wool catches and holds the dyes, so the colors are quite fast. I love a couple of MSM’s wool quilts. One, made around 1825, is so modern in its feel that I made a ¼-sized version of it five years ago, my first quilt. And there’s another, from around 1830, from Scarborough, that has octagons of black and orange that frame a green and turquoise center. It’s zingy. The colorways of the 1830s were riotous, not at all like the sepia-toned notions about the past. I compare them to the colors of the early 1970s. Ka-Pow! But since I am determined to cast a blind eye to quilts from MSM, I would choose a wool quilt from the North Haven Historical Society. Rachel Calderwood made it around 1835. It is black with an open grid of green in the center, and at every intersection of the grid there are orange squares. It’s striking, and the quilting is lovely.

Kenny: Are there any aspects to quilting history that are peculiar to Maine?

Laurie: Are you familiar with the book, Big House, Little House, Back House, Barn by Thomas Hubka? Maine turns out to be the epicenter for those connected farm buildings, but they are present elsewhere in Northern New England, as well. Maine quilt traits are like that, too: each of the styles is present elsewhere in the area but more popular here. A lot of Maine quilts have “cut corners,” where the bottom corners of the quilt are missing. This enables the quilt to wrap neatly around the bed posts at the foot of the bed. Maine was also the center of what today is called “quilt as you go,” or “potholder quilts.” Each block was finished completely: cut, stitched, backed, quilted, bound. Only then were the blocks sewn together to make a quilt. You see it most in the mid-1800s, but there is currently a revival of the practice. I think my favorite Maine quilt trait is a tendency to not know when to stop when making a quilt block: there will be a central block, with a border around it, and often a frame around that. MSM has a quilt that has all three of these Maine traits: it was made around 1845 in Dresden, Maine. It has cut corners, and half of the blocks have extra borders. The quilt is a little wonky because many women made blocks, potholder-style, and not all of them are exactly the same size. There’s also a short-lived Maine style of wool quilt that appears around 1800 and disappears by 1840.

Kenny: This book is simultaneously beautiful, engaging, and informative. I know you are a modest person but the quality of this book must pose a dire threat to your modesty?

Laurie: Thank you! My joy in the book was tempered by a long wait for its release. Thanks to Covid it’s a year late. Research on the book took about ten years to complete, and I discovered more while the book was on hold, so I was able to update the text (thank heaven my production editor is a quilter. She was very indulgent). That underscores the fact that research will continue, and down the road my work will need to be updated. The figures are central to the importance of the book. There are over 150 quilts pictured, and about 275 figures. I had 300, but was told that was too many. So I had to cut 25 detail shots, alas. We received a grant from the Coby Foundation to photograph the quilts. Mike Taylor did the photography. I wish the illustrations could have been bigger, but then the book would be much longer and more expensive so…. it’s a compromise!

And I couldn’t have done it without great colleagues. Two nationally recognized quilt historians and a collector of Maine quilts contributed essays and an introduction to the book. And of course, the acknowledgments section is a whopping four pages of small font, and I am sure I forgot to thank somebody. It was a great experience to be able to work with so many people, and I made a lot of friends along the way.