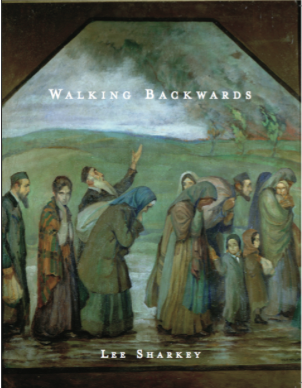

On Oct. 20, longtime University of Maine at Farmington professor (now retired) and acclaimed poet (not retired) Lee Sharkey, will be launching her new book Walking Backwards in Farmington at DDG Booksellers. I checked in with Lee about her latest poetry collection.

Kenny: If you could have one painter and one writer from the past read your new book of poems who would they be?

Lee: The painter would have to be one of the artists—e.g. Paul Klee, Franz Marc, August Macke, George Grosz, Wassily Kandinsky—condemned by Hitler and his “Minister for Cultural Enlightenment” Joseph Goebbels as creators of “degenerate art.” The destruction of much of their work during the Nazi era is just one aspect of the cultural erasure that I confront in Walking Backwards. For related reasons, the writer would be the great Yiddish-language poet Abraham Sutzkever, whose work would be more widely celebrated had he not written in whose speakers were largely annihilated during WWII. How honored (and terrified) I would be to have them read my work.

Kenny: In the 8th Cautionary you make an interesting assertion that “any sound that a sound can make has lost its history.” Do you mean to say that history is mute or that it is entirely received rather than pronounced?

Lee: The sentence may have multiple, and simultaneous, and even contradictory readings, since poetry’s explorations often take place on the plane of ambiguity.

On a literal level, suppressing language is a common tool for suppressing the stories people tell and coalesce around. When there is no tongue to tell their history in, how will it be remembered? The near-erasure of the Yiddish language is one, extreme, example. But consider also how conquering powers change street names when they take control of a city. The idea is to inscribe a new set of linguistic reference points that efface the reference points of the conquered population.

On a psychological level, you might read the sentence as emerging from trauma: the traumatized person speaks but the words go dead in the mouth, lacking their former associations with a lifetime’s experience. This, of course, is a dangerous state for both an individual and a culture; it results in chronic unease and opens the door to demagogues.

On an existential level, staring into the face of history and acknowledging the evil human beings are capable of can render us speechless. Language is all we have to make sense of what happens, but it’s often inadequate to the task. Poets have confronted this paradox all along in their work but with heightened consciousness, perhaps, in light of the mass destructions of the 20th and 21st centuries. I think this accounts for the silences, the white space, in many modern and contemporary poets’ work.

Kenny: Speaking of history does this volume have an overarching historical narrative. Also, is its narrative applicable beyond its particular roots in Jewish letters and experience?

Lee: In Walking Backwards, I aimed to create a simultaneous present where different historical eras and figures could converge. Biblical characters, Israeli soldiers and Palestinians waiting at a checkpoint, the 12th century Sephardic scholar Maimonides, and several poets whose voices were annealed in the Holocaust are drawn into dialog with the speaker of the poems (me/not me) and each other. The scene shifts to Eastern Europe in the second half of the book, where the speaker of the poems walks backwards into the past in order to retrieve its remnants. Although these particulars arise from the Jewish experience, I hope the journey the book undertakes through parable, myth, and history to recover something essential to our understanding of the present—and dare I say the human condition—is relevant beyond that particular context.

Lee: In Walking Backwards, I aimed to create a simultaneous present where different historical eras and figures could converge. Biblical characters, Israeli soldiers and Palestinians waiting at a checkpoint, the 12th century Sephardic scholar Maimonides, and several poets whose voices were annealed in the Holocaust are drawn into dialog with the speaker of the poems (me/not me) and each other. The scene shifts to Eastern Europe in the second half of the book, where the speaker of the poems walks backwards into the past in order to retrieve its remnants. Although these particulars arise from the Jewish experience, I hope the journey the book undertakes through parable, myth, and history to recover something essential to our understanding of the present—and dare I say the human condition—is relevant beyond that particular context.

Kenny: If you were having a cup of coffee by yourself and had your book on the table what page would you go to first?

Lee: That depends upon the day. Today, with the election in mind, I might turn to “The City.” Before I composed it, I had been thinking about the vision of the City on the Hill and reading about Cities of Refuge in biblical-era Palestine, where those who committed unintentional manslaughter might go and be safe from prosecution. Months after I completed the manuscript, I realized that the quest for a city “with water for cleaning and drinking” and “bread to quiet hunger,” a city free from violence and hunger and welcoming to the stranger, was the thread that held the book together.

Kenny: Walking Backwards is a great title for the volume. Was there a runner up?.

Lee: Never. The line “Tonight I am walking backwards” came to me in a dream that led to my spending parts of two summers in Vilnius, Lithuania. There I wrote the poem “In the Capital of a Small Republic” in which the image recurs. I knew at that point what a big fish I had hooked and that the manuscript would organize itself around it.

Kenny: Thanks Lee.

Lee: I’m looking forward to the 20th!

A Poetry Reading and book signing by Lee Sharkey for Walking Backwards, 2016, Tupelo Press, will be held 7 p.m. on Thursday, Oct. 20 at DDG Booksellers in downtown Farmington.