By Paul Mills

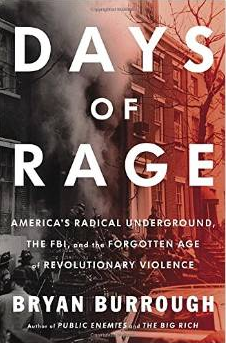

The recently concluded Boston Marathon bombing trial has been yet a further reminder of the stunning impact of terrorism on American soil. It’s been accompanied also by the release of a new book, Days of Rage, one that alerts us all to the fact that the neither the marathon bombing nor other expressions of politically inspired violence is anything new to New England.

Bryan Burrough, a former Wall Street Journal reporter and correspondent for Vanity Fair, has in this nearly 600-page work, told the saga of America’s radical underground during the 1970s. It’s a story whose use of violence during that time became almost routine. It was so common in fact that bombings were far more widespread than they are today even though much of the violence was little noticed at the time. The new book is also a story that includes a focus on New England, particularly Maine.

Many in the state today do recall that Maine was a jumping off point and haunt of the ring leader of the 9/11 terrorists, Mohamed Atta. Atta spent most of the 24-hour period before the World Trade Center bombings in southern Maine. He had also been spotted several times the previous year working the computer terminals at Portland’s public library.

Few, however, in Maine today are aware of the 1970s terrorist bombers to which the Pine Tree State played host. Burrough’s new book is a well written reminder of such dramatic episodes.

Just a quarter century before the Sept. 11, 2001 bombings, in 1976, two 27-year-old Maine-based men were in the midst of a four-month stint on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List. Two other Mainers with whom they were associated were already in custody. All four were charged with an array of terrorist bombing plots whose targets included Boston’s Logan Airport, a National Guard Armory, Central Maine Power Company, and a courthouse in Massachusetts.

The FBI’s initial interest was piqued by an explosion in May 1976 at CMP’s Augusta headquarters. An anonymous admonition soon issued that included the pronouncement of a Marxist overthrow agenda coupled with a warning of future violence.

Three days later, a $15,000 hold up at the Orono branch of Depositors Trust Company enabled the group to purchase an additional arsenal of dynamite, blasting caps, and timing devices.

By the first two days of July, the plot crossed state lines. The outcome: four explosions, the Newburyport Superior Courthouse, an empty Eastern Airlines jetliner at Logan Airport, a National Guard truck in Dorchester, all in Massachusetts and then the Seabrook, New Hampshire post office.

Meanwhile, the FBI was developing the kind of intelligence it no doubt wished it had but evidently didn’t at the time of 9/11 and the 2013 marathon bombings: the benefit of leaks from a confidential inside informant, alerting it to the group’s future plans.

As the nation was riveting its eyes on the bicentennial observance, the FBI was training its sights on a Cushman Street apartment near Portland’s Western Promenade. This had become a headquarters for the group.

Just before 10 p.m. Saturday evening July 3, 1976 on the eve of the nation’s bicentennial, three of the four are spotted leaving in a brown Plymouth from the apartment. Shortly after midnight, after the car stops to let out two of its passengers near the Topsfield State Police Barracks in Massachusetts federal and state agents give chase. The car eludes the agents but shortly after it is abandoned, agents seize 46-sticks of dynamite, some of it wired to timing devices. (Another 600 pounds of the group’s dynamite was later recovered just outside Portland.)

The driver, Munjoy Hill native Joey Aceto, then 23, is soon apprehended. He agrees to cooperate with authorities. (He was not, however, the inside informant who had tipped off the FBI). He reveals that the group had hoped to use its newly purchased arsenal against both A & P as well as Polaroid Corporate offices in the Boston area. Though a second suspect is also soon arrested in Portland, authorities nevertheless remain stymied by the other two, who remain at large and on the Most Wanted list until late October.

At the trials of the three others in Portland’s federal district court Aceto is a key witness.

Though some of the most prominent trial attorneys in New England came to their defense and though in some of the trials partial acquittals were achieved, each of the four is nevertheless convicted of transporting explosives in interstate commerce with knowledge that they would be used to intimidate individuals and damage or destroy property.

Though some of the most prominent trial attorneys in New England came to their defense and though in some of the trials partial acquittals were achieved, each of the four is nevertheless convicted of transporting explosives in interstate commerce with knowledge that they would be used to intimidate individuals and damage or destroy property.

The second of the cases, a three-week trial of 27-year old Richard “Dickie” Picariello, featured the longest sequestration of jurors in the history of the federal court in Maine up to that time.

Picariello would spend the next two decades behind bars, both for some of the bicentennial-related charges and also on other criminal convictions. Now 66, he was most recently believed to be working in a family fishing business in Florida.

Aceto, whose life ended with his death at age 61 from natural causes in a Montana jail just over a year ago, stayed in the public eye much longer, this despite a federally sponsored change of name and identity. Released from federal prison in 1979 with a new last name, “Balino,” a series of burglaries and robberies in Arkansas landed him back in prison where he was then convicted of stabbing a fellow inmate. He won a release there in 1997.

Aceto wound up in prison again – this time on a 210 year sentence – after being convicted for the aggravated kidnapping of a former girlfriend and an attempted homicide of her new boyfriend that occurred in Montana in 2000.

More nationally renowned than either Aceto or Picariello but who for a time worked closely with them, was Sanford native Raymond Luc Levasseur, to whom Burrough’s book devotes considerable attention. For Levasseur, according to Days of Rage led “the most unusual of the 1970’s era underground groups.” It consisted of three blue-collar couples and their nine children.

Levasseur was implicated in eight Boston area bombings in the late 1970s including one that injured 22 people at the Suffolk County Courthouse and with nine bombings of both corporate and military related sites in the New York City area during the early 1980s. After seven years as a fugitive on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list and living at large with his wife and three children under a series of assumed names, he was captured in 1984. By 2004, he was released on parole after serving nearly half of a 45-year prison sentence.

He is now back in Maine, living outside Belfast where, at age 69, he lives quietly publishing articles on the Internet about various social and political issues, a pursuit reminiscent of his time as a bookstore owner on Portland’s Congress Street during the ’70s.

To be sure, Burrough’s book also casts his spotlight outside New England. Patty Hearst’s kidnapping by – and her bizarre conversion to – the Symbionese Liberation Army is given its due as are Weather Underground leaders Bernardine Dorhn and Mark Rudd. All landed on their feet – after some years as fugitives and then in prison – eventually adopting conventional within-the system lifestyles. Dorhn and Rudd, for example, put in more time as college professors than they had earlier served in prison.

A reason why their 1970s identities have been largely forgotten is because their tactics proved ineffectual. Their political agenda was never fulfilled. It was Ronald Reagan – hardly the Che Guevera disciple they might have hoped for – elected once the decade had come to an end. Moreover, despite the widespread incidence of violence associated with their causes, most sought to avoid taking the lives of innocent victims, a feature that sets them apart from many of the 21st century protagonists of such tactics.

Peaceful rather than violent advocacy is now embraced by nearly all the 1970s Days of Rage revolutionaries. As Burroughs observes, what Levasseur now publishes on the Internet receives, “exponentially more exposure than any of the communiqués he issued after his many bombings.”

Levasseur’s abandonment of violence is typical of the present mindset of nearly all such 1970s radicals still alive today. Nevertheless, the episodes of such aggression that characterized the tactics of the era, as so well documented in Burrough’s Days of Rage, are ones that should remind us that they are a phenomenon that is not new to either Maine or elsewhere in America.

Paul H. Mills, son of the late Peter Mills, who was a prosecutor in the 1976-1977 bombing trials, is a Farmington attorney well known for his analyses and historical understanding of public affairs in

Maine. He can be reached by e-mail: pmills@myfairpoint.net.

Thanks, Paul.

It’s good to be reminded that even Maine can have passionate misguided violence among its citizens. We are wrong to believe that Arab states invented terrorism.

What’s wrong is how the Arab states have embraced terrorism..

And……they probably DID invent it.

Denial is foolish.